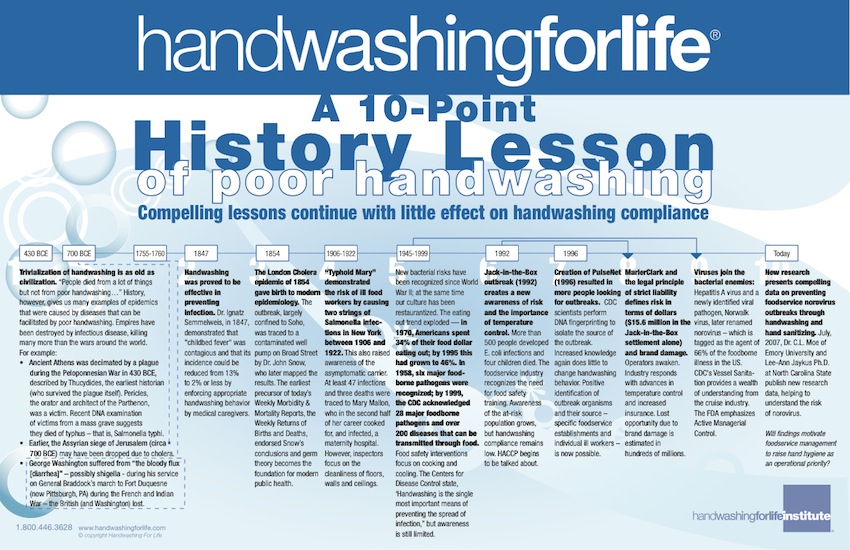

Compelling lessons continue with little effect on handwashing compliance.

A 10-Point History Lesson of Poor Handwashing

Handwashing has been trivialized for centuries. There have been events in the course of history which should have changed handwashing behaviors but didn’t. This review is intended as a reflection on today’s hand hygiene behaviors in response to these two questions: Are we still underestimating the outcomes of underwashing? Are we ready to care enough about others to wash our hands?

- Trivialization of handwashing is as old as civilization. “People died from a lot of things but not from poor handwashing…” History, however, gives us many examples of epidemics that were caused by diseases that can be facilitated by poor handwashing. Empires have been destroyed by infectious disease, killing many more than the wars around the world. For example:

- Ancient Athens was decimated by a plague during the Peloponnesian War in 430 BCE, described by Thucydides, the earliest historian (who survived the plague itself). Pericles, the orator and architect of the Parthenon, was a victim. Recent DNA examination of victims from a mass grave suggests they died of typhus – that is, Salmonella typhi.

- Earlier, the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem (circa 700 BCE) may have been dropped due to cholera.

- George Washington suffered from “the bloody flux [diarrhea]” – possibly shigella – during his service on General Braddock’s march to Fort Duquesne (now Pittburgh, PA) during the French and Indian War – the British (and Washington) lost.

- The London Cholera epidemic of 1854 gave birth to modern epidemiology. The outbreak, largely confined to Soho, was traced to a contaminated well pump on Broad Street by Dr. John Snow, who later mapped the results. The earliest precursor of today’s Weekly Morbidity & Mortality Reports, the Weekly Returns of Births and Deaths, endorsed Snow’s conclusions and germ theory was to set to the stage for modern public health.

- Handwashing was proved to be effective in preventing infection. Dr. Ignatz Semmelweis, in 1847, demonstrated that “childbed fever” was contagious and that its incidence could be reduced form 13% to 2% orless by enforcing appropriate hand-washing behavior by medical care-givers.

- “Typhoid Mary” demonstrated the risk of ill food workers by causing two strings of Salmonella infections in New York between 1906 and 1922. This also raised awareness of the asymptomatic carrier. At least 47 infections and three deaths were traced to Mary Mallon, who in the second half of her career cooked for, and infected, a maternity hospital. However, inspectors focus on the cleanliness of floors, walls and ceilings.

- New bacterial risks have been recognized since World War II; at the same time our culture has been restaurantized. The eating out trend exploded – in 1970, Americans spent 34% of their food dollar eating out; by 1995 this had grown to 46%. In 1958, six major foodborne pathogens were recognized; by 1999, the CDC recognizes 28 major foodborne pathogens and over 200 diseases that can be transmitted through food. Food safety interventions focus on cooking and cooling. The Centers for Disease Control state, ‘Handwashing is the single most important means of preventing the spread of infection,” but awareness is still limited.

- Jack-in-the-Box outbreak (1992) creates a new awareness of risk and the importance of temperature control. More than 500 people developed E. coli infections and four children died. The foodservice industry recognizes the need for food safety training. Awareness of the at-risk population grows, but handwashing compliance remains low. HACCP begins to be talked about.

- Creation of PulseNet (1996) resulted in more people looking for outbreaks. CDC scientists perform DNA fingerprinting to isolate the source of the outbreak. Increased knowledge again does little to change handwashing behavior. Positive identification of outbreak organisms and their source – specific foodservice establishments and individual ill workers – is now possible.

- MarlerClark and the legal principle of strict liability defines risk in terms of dollars ($15.6 million in the Jack-in-Box settlement alone) and brand damage. Operators awaken. Industry responds with advances in temperature control and increased insurance.

- Viruses join the bacterial enemies: Hepatitis A virus and a newly identified viral pathogen, Norwalk virus, later renamed norovirus – which is tagged as the agent of 66% of the foodborne illness in the US. CDC’s Vessel Sanitation provides a wealth of understanding from the cruise industry. The FDA emphasizes Active Managerial Control.

- New research presents compelling data on preventing foodservice norovirus outbreaks through handwashing and hand sanitizing. July, 2007, Dr. C.L. Moe of Emory University and Lee-Ann Jaykus Ph.D. at North Carolina State publish new research data, helping to understand the risk of norovirus. Will foodservice management be motivated to raise hand hygiene as an operational priority?

Dion Lerman, Education & Training Director

Handwashing Leadership Forum

NB:Article originally published in Food Safety Magazine, December 2007/January 2008.

- Diamond, J., Guns, Germs, and Steel: The fates of human societies. NY: Norton, 1999.

- History of the Peloponnesian War ii, 47–55, and Papagrigorakis, M. J., Christos Y., Synodinos, P.N., and Baziotopoulou-Valavani, E. “DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 10 (2006): 206-214. ISSN 1201-9712.

- Bollet, A.J., Plagues and Poxes: TheiImpact of human history on epidemic disease,. New York, Demos, 2004

- The health and controversial death of George Washington – Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, Feb, 2001 by Charles B. Witt Jr. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BUM/is_2_80/ai_76636540/pg_1, accessed 9/20/07

- Johnson, S., The Ghost Map: The story of London’s most terrifying epidemic – and how it changed science, cities and the modern world. New York: Riverhead/Penguin, 2006.

- Risse, G.B., Semmelweis, Ignaz Philipp. Dictionary of Scientific Biography (C.C. Gilespie, ed.). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1970-1980.

- Judith Walzer Leavitt, Typhoid Mary: Captive to the public’s health (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996) 16-17.

- Dumagan , JC, and Hackett, JW, Almost half of the food budget is spent eating out, Food Review, Jan-April, 1995

- Burdon, K.L., Textboook of Microbiology, 4e. NY: Macmillian, 1958.

- Mead, PS. and, Slusker, L., Dietz, V., McCraig, L.F., Bresee, J.S., Shapiro, C., Griffin, P.M., Tauxe, R.V., Food-related Illness and death inthe United States. Emerging Infectious Diseases 5:5, 607-625. Sept-Oct 1999. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol5no5/mead.htm

- Bryan FL. Diseases transmitted by foods (A classification and summary). 2nd edition. U.S. Department of Heath and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control. Atlanta:HHS Pub No. (CDC) 84-8237, 1982.

- Garner JS, Favero MS. CDC guidelines for the prevention and control of nosocomial infections. Guideline for handwashing and hospital environmental control. AJIC. 1986;14(3):110-115.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Update: Multistate Outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Infections from Hamburgers–Western United States, 1992-1993. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. MMWR 42(14):1993 Apr 16

- http://www.marlerclark.com/

- Mead, op cit.

- Tseng, FC, JS Leon, JN MacCormack, J-M Maillard and CL Moe (2007) Molecular epidemiology of norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks in North Carolina, United States: 1995-2000. J Med Virol. 79(1):84-9